I finally got an ‘admit one’ ticket to the circus of Italian politics. Well, sort of.

I voted. In a way.

Milan is holding primary elections for center-left mayoral candidates and immigrants can join the fun, too.

No matter that those same non-Italian citizens cannot actually vote in the national May elections.

No matter that those same non-Italian citizens cannot actually vote in the national May elections.

The scattered left parties, up against Berlusconi’s record-holding government, have brought a new concept to the Italian political system: primary elections.

Since they need numbers, immigrants resident here for at least three years can participate in these primaries.

The reasoning? Immigrants will vote for left, because the left will promote fair immigration laws. Ignoring, of course, that the cornerstone of those laws, the Turco-Napolitano, is a quite conservative product of the left.

Voting is a major part of life in any country, but in Italy there were so many things to vote for — what with the government falling every three weeks and referendums all the time — that it became a constant cultural activity.

As an extracomunitaria, as non-EU citizens are called, I never got to join the fun.

I would follow, puppy-like, Italian friends into grade schools and wait outside classrooms while they cast about for a new leader or expressed an opinion on hunting. But I was still an outsider.

Now it was my turn.

I wait behind two elderly, fur-coated signore outside a white plastic tent put up for the occasion in the square.

My neighborhood borders Chinatown, but I am the first non-Italian to vote here. The first two volunteers are at a loss and I am shown to Paolo, a jaunty middle-aged man in a flat cap and puffer jacket. He checks my ID card, looks at a photocopy of my stay permit and stands over another volunteer to make sure my voter form is filled out properly.

They take my name, place of birth (inevitably pronounced San-Fran-Chees-ko) and tell me I must also fork over a donation, of at least a euro, for the privilege. Sure, I say, swiping a few Pocket Coffees from a tray of chocolates offered to voters for the trouble.

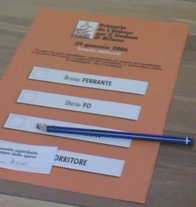

I take my bright orange ballot over to a little desk that, in a vague nod to privacy, has two little 8 x 10 pieces of cardboard around it.

There are four candidates:

Bruno Ferrante, former head of the police department who bills himself as a “servant of the Italian state.”

Milly Moratti, current city councilor, who would run against the only other female candidate, her conservative sister-in-law and former education minister Letizia Moratti.

Dario Fo, Nobel prize winner for literature, who at 80 would perhaps be the oldest mayor in Italy.

Davide Corritore, a congenial-looking 47-year old with background in finance background for the Union party.

On my way out, I ask Paolo when he thinks immigrants will be able to vote for real. “Chissà?” Who knows, he says, shrugging in typical Italian fashion.

Perhaps turning out for the old college try is what political participation is really about in Italy.