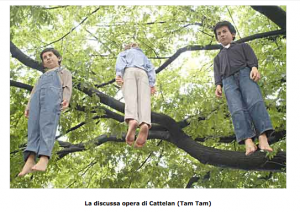

Franco De Benedetto, a Milan construction worker who climbed a tree to “liberate” artist Maurizio Cattelan’s hanging dummy children, was sentenced to two months in prison for his crime against art. Continue reading

Franco De Benedetto, a Milan construction worker who climbed a tree to “liberate” artist Maurizio Cattelan’s hanging dummy children, was sentenced to two months in prison for his crime against art. Continue reading

Author Archives:

Peace: just another flag?

Tattered and faded, a few rainbow peace flags continue to fly from balconies across Europe.

Tattered and faded, a few rainbow peace flags continue to fly from balconies across Europe.

The flag proclaiming “Pace” (Peace) in Italian made its way to Germany, Austria, Switzerland, Spain and Brussels, first to protest the war in Afghanistan and later the war against Iraq. A symbol of anti-war sentiment bandied about during hundreds of demonstrations, the first were seen during protests of the 2001 G8 meeting in Genoa Italy. Continue reading

Milan’s Double Vision

There are now two marble plaques commemorating the death of anarchist Giuseppe Pinelli in Piazza Fontana. In 1969, Pinelli fell to his death from the fourth-story window of police headquarters during an interrogation for the Piazza Fontana bombing, which killed 16. One tablet, installed by city officials overnight Continue reading

There are now two marble plaques commemorating the death of anarchist Giuseppe Pinelli in Piazza Fontana. In 1969, Pinelli fell to his death from the fourth-story window of police headquarters during an interrogation for the Piazza Fontana bombing, which killed 16. One tablet, installed by city officials overnight Continue reading

I Say Tortilla, You Say Piadina – Let’s Eat

The last thing I expected when I moved to Florence, Italy was to lose 12 pounds in a few weeks.

Surveying the gaunt faces during a morning orientation session for a year-long study abroad program, the director noted that many of us had dropped the “Freshman 15,” the weight newcomers shed after putting scruffy Converse sneakers on Italian soil.

Yes, in the land of pasta, pizza, prosciutto and gelato.

How could this be?

Far from some anti-Atkins miracle, it came down to a severe lack of culinary skills. I, for one, had spent my college years in San Francisco staving off hunger by slapping together a few tortillas with cheese with perhaps a guacamole chaser for a meal. Many meals.

This was not going to sustain daily schlepping on foot to the sights of a city with 600 years of art treasures. The nearly constant wooziness — equal parts Stendhal syndrome and hunger — reminded me that I did not know how to live in this beautiful, bewildering place.

Many an intrepid cultural exploration starts at a foreign supermarket and my trek to an Esselunga across town, one of the few supermarkets around then, was a revelation. I had never seen a supermarket that stocked only food.

Just the raw materials. There wasn’t any cereal, frozen pizzas or canned soups. And not a tortilla in sight. I walked the cramped aisles in amazement, wondering how long it would take to grasp the subtle differences in 63,000 different shapes of pasta. The variants on tomato products also mystified me: tubes of tomato paste, a plethora of different types of canned whole tomatoes, cans of tomato pulp.

Left to my own devices, there was only so much crispy burnt garlic and undercooked penne I could eat. Gelato was daily sustenance and even that didn’t keep me from sporting the oversize look nearly a decade before it came into fashion.

Some months later, my Italian language exchange partner Barbara invited me to her hometown Faenza, in Emilia Romagna, for the weekend. I was eager to learn more about regional differences in Italy — Barbara’s slightly lispy accent was already so different from the open-mouthed hah-sounds of the Florentines — and hopefully put on a pound or two thanks to her doting grandmother.

On Saturday night, we drove out to a trattoria that looked like an abandoned farm house where we found two places at the end of a long, communal table and drank fizzy red Lambrusco wine.

Then baskets of flour tortillas, cut into triangles, came out of the kitchen. Tortillas? In Italy?

“No,” Barbara explained: Piadine. Not tortillas.”

I asked what they were made of: flour, lard and salt.

Whatever. Call them piadine, I know they are tortillas. Besides, I’m too hungry to argue.

The platters of toppings that followed were a different matter: creamy squaquerone cheese, smoked scamorza, prosciutto cotto and crudo, arugula, spinach, mushrooms. In triumph, I lifted a triangle sagging with eggplant to my mouth knowing I would never go hungry again.

Barbara’s grandmother, Isotta, nearly cried with laughter as I related in approximate Italian my delight in their local specialty. She had been plying me with pumpkin tortelloni and roasted lamb with peas, true regional masterpieces, and here I was raving about peasant food. Isotta explained that piadine were farmer’s daily bread but nearly went extinct until the 1960s when they made a comeback as “Italian fast food.” Now nearly everyone bought them instead of making their own at home and they were staples at all-night kiosks.

When the weekend came to an end, I was grateful to have an unfashionable, Everest-ready backpack (for some reason, life in Europe seemed to require sturdy hiking gear) roomy enough to export my discovery.

There were piles of ready-made piadine (as foreign to Florence as tortillas then) and a testo, a terracotta disc to heat them up. Isotta had showed me how to make them and while I limited my participation to nodding while she kneaded, I learned how to heat them up properly.

With the testo over a gas flame, the piadina cooks a few minutes on one side until brown spots show up, you prod the bigger bubbles down with a fork, then just flip over and repeat. Slather some cheese, a few slices of prosciutto and ecco! you’ve got a meal. While it wasn’t exactly cooking, piadina slinging did wonders for my morale and my waistline. I stuck it out in Italy, learning to cook among other things and that perplexing trouble of trying to gain weight is only a distant memory.

Piadine/Tortillas:

- Substitute regular flour tortillas (no non-fat versions!) for best results.

- Leave cheese at room temperature for at least 10 minutes so it will melt without burning the tortilla.

- Heat both sides of the tortilla on a griddle or non-stick pan, lower heat and add thinly-sliced cheese, warm for about 10 seconds, then add meat and heat for another circa 10 seconds. Take off griddle, fold in half, cut and serve.

Unlike many Italian dishes there are no steadfast rules here, but avoid sharp or salty cheeses with cured meat — brie and prosciutto, for example. Some winning combinations:

- Mozzarella and crudo, mozzarella and tomato, brie and crudo, gorgonzola and walnuts, prosciutto (cotto or crudo) and fontina.

- Cheese: provolone, mozzarella, fontina, brie, gorgonzola

- Meat: prosciutto (cotto, crudo) or cured meats such as speck, bresaola.

Veggies: arugula, tomato, spinach and grilled eggplant, bell pepper or zucchini.

Italy’s Art Watch

A new manual may help stem the tide of precious artefacts stolen from Milan churches. Penned by Vito Cicale, officer with the national police unit for protecting cultural heritage, the how-to book launched recently at a conference on art safety in churches at the Diocese Museum. Continue reading

Color Milan Beautiful

Grey, foggy Milan is about to get a lift with a new city color scheme.

Grey, foggy Milan is about to get a lift with a new city color scheme.

Working with architecture professors from the Politecnico University, officials developed a “color plan for urban decor” in a palette that includes red and yellow.

These primary colors would mean an extreme makeover for light poles, clocks, trash cans and benches painted grey, black and kelly green respectively. Continue reading

Are Italian superstitions? You bet

I managed to change a train ticket in Venice at the last minute. It was a major triumph.

First Jabba the Hut behind the counter puffed at me, saying he wasn’t sure he could change my Internet ticket. So I Spaniel-eyed him.

He reconsidered. Then punched in a few things with monstrously fat fingers and waited for the computer’s verdict.

“You shouldn’t have fought with your boyfriend,” he commented, smiling through a row of green-gray teeth. Because, of course, the only reason a woman would need to get the hell out of Dodge in a hurry would be a love spat.

Anyway, he managed to get me on a Cisalpino — great but rare Swiss trains — leaving in 10 minutes. I said “grazie” and ran.

Two stops out of Venice I find myself sitting across from Erica, a woman I take a class with here in Milan and her sister, visiting from London.

Coincidence?

No, Fate! It’s a random Thursday and a trip neither of us ever take. I shouldn’t have been on the train. The seats are reserved, the train is packed. It definitely means something.

Erica fields a mobile phone call from her boyfriend who insists we play the lottery.

The lottery, or lotto, is one of the things that unifies Italians. In fact, in the 1500s — centuries before there was an Italian state — Florentines were already holding lotteries with cash prizes.

How do you know which numbers to pick?

Well, if you’re lucky like we were, life hands them to you. Her man implored us to play our seat numbers (71,72,78) and the carriage number (8).

It struck me as a good idea. The only other time I’d ever played the lotto using this method it worked, rectifying a bad vacation. A bed and breakfast in Lecce had requested a deposit –1/4 of the total plus two or something — wired down before the stay. It was an odd figure, say €138 euro.

On arrival we promptly managed to knock down a low wall in the B&B’s garage while trying to park. A guy in cement-spattered overalls trotted by the next day with an estimate: €138 euro. My Italian companions insisted on playing the 1-3-8 combination — we won €200.

There are many other ways of finding your lucky numbers, the main one is dream interpretation. Developed around the time of the lottery in Florence, a book out of Naples called the “smorfia” (book of numbers) is a guide to turning figures in your dreams into winning numbers.

I’ve never had much luck with it. Perhaps the smorfia only works if your dreams are a little less impregnated with pop culture. Many a time I have pored over it wondering how to place H.R. Pufnstuff or if Alice from “The Brady Bunch” qualifies as dead woman walking.

Anyway, now I’ve got my numbers and if you don’t see me on Thursday, I’ve hit it big.

Going anywhere? Check Italy’s strike predictor first

In most countries, people check the weather forecast before leaving the house.

They may also check traffic. Or, with skyrocketing gas costs, prices at the pump.

In Italy, people check the strike-o-meter, or scioperometro, a strike forecast published on the Internet.

Italians, with strong union representation, are some of the most active strikers in all of Europe. They are fourth with an average of 113 days lost per 1,000 workers in protests.

As a freelancer who usually works from home, they don’t affect me that much. But the law of travel in the Bel Paese states that if you have to go anywhere, especially from one city to another, more than once in a month you’ll get nailed by some sort of transport strike.

Often they pass for civilized – called and announced well in advance and only for a few hours – but if you get caught in one, it is a real nightmare.

I’m still working through the scars from being stranded at Malpensa airport for seven hours in an attempt to get to Budapest. The strike per se only lasted two hours. Unfortunately, the only other flight to Budapest was five hours after that.

Malpensa (whose name aptly translates into “bad thought”) has to be one of the biggest, emptiest, cruddiest airports around.

Almost everything (including restaurants, clothes shops, food shops, most newsstands and the spa) had shuttered on a Saturday afternoon. Opting to take refuge at Burger King nursing a Moretti beer was preferable to hanging out at either the pharmacy or the chapel. Even worse? If I had checked beforehand, I could’ve booked directly on the next flight.

The genius behind the strike-o-meter is that it groups all the strikes into one national calendar, so you don’t get caught out by some small union paralyzing traffic in Rome.

Here’s this month’s forecast:

May 5

Airport personnel strike in Milan, noon to 4 p.m.

24 hour national train strike

May 12

National airport personnel strike, noon to four except in Rome, 10-6 p.m.

May 23

Alitalia pilot strike, 10-6p.m.

You have been warned.

Signorina, encore!

A couple of days ago, I was hauling a stash of groceries home with my bike. As I passed a cafe, a guy sitting outside nursing a cappuccino yelled, “Signorina, look out for the bag!”

It was a good thing he did, the plastic bag was about to rip from the handlebar scattering a load of pears, some camone tomatoes and a bottle of Vermentino on the square.

I wasn’t so surprised at the shouting: once you leave home, everyone is in your business in Italy.

The barista downstairs thinks nothing of mentioning that a tanning bed session might do you good, the newsstand lady will comment that pink really isn’t your color, the doorman will ask pointed questions about certain contributions to the recycling bins, leaving you agonizing over whether condom packets count as aluminum foil.

It was the signorina thing. That gets me.

As in most Romance languages, in Italian there is a distinction between a young, unmarried woman and a married, older one.

Just two forms of address, signorina (unmarried) and signora (married).

Paola, a self-declared feminist, taught me Italian when I was in my early 20s. She explained since the sexual revolution, women under 18 are “signorine” after that we all had the right to “signora.” Married or not.

“Don’t let them ‘signorina’ you,” she explained. “It’s a subtle put-down.”

Despite being more or less old enough to have a daughter shifting from signorina to signora, I still have a schizophrenic identity.

I’m resigned to signorina at the bank. And signora for the wafer-thin girls in trendy shops. I morph into signorina when the flirty guys try to sell me more of that Sicilian cheese with peppercorn at the market and back to signora when a teenager apologizes for bumping into me on the metro.

What surprised me about this signorina? The savior of my tomatoes wasn’t that old — unless you have seven children in tow, you’ll never get a signora out of anyone over 50 — maybe late 40s. And he had no reason to flatter. For a split second, I was still on signorina ground.

Newsweekly Io Donna ran an editorial about the “signora – signorina” debate, suggesting when someone asks which category we fall under, the pithy response should be: “dottoressa,” meaning one has a university degree.

Fair enough. Italian doesn’t lend itself to hybrid forms — like Ms. in English — and it would take the emphasis off marital status. Until that happens, I won’t get my knickers in a twist over the occasional, accidental, signorina.

The uncertain singalong: “Bella Ciao!”

I don’t remember the first time I heard partisan anthem “Bella Ciao,” but the first time it meant something was during a Fourth of July concert at the American Consulate in Florence.

Nehemiah Brown, one of the most inspiring expats I know, runs a Gospel school there and put it in a gig he did for diplomats and locals.

The song is about waking up one morning with Fascists at the door, deciding to join the resistance movement, knowing it means probably not coming back alive, but ultimately the fight for freedom is worth the price.

Each verse ends with a punchy “Bella ciao, bella ciao, bella ciao ciao ciao!” as the partisan says goodbye to his girl.

So the Americans who didn’t know Italian — much less the cultural context of the song — started clapping along with the “bella ciao” part.

And wondered why the Italians winced at first, then sang along too.

When I asked Nehemiah about it, he just laughed, admitting he knew the kind of effect the song would produce.

Why were the Italians — and anyone who understood — uneasy?

Italians aren’t big on anthems; they still don’t have an official national one, believe it or not.

And “Bella Ciao” has become the de facto song for celebrations of April 25 Liberation Day, as in liberation from the Fascists with the arrival of U.S. troops.

With the exception of Mussolini’s granddaughter Alessandra and her political cohorts, not many Italians have black shirt nostalgia, but “Bella Ciao” has since become a hymn mostly associated with the extreme left — and that kind of affiliation makes a lot of Italians uncomfortable. (The motto for one media collective named in honor of the song is: “To rebel is right, to disobey is a duty, to act is necessary!”)

Nehemiah, sidestepping the political implications with the immunity of a foreigner, used to teach it to Italian kids at grade school. He was surprised to find the kids didn’t know it but that even conservative parents were moved to hear their offspring belt out this historic ditty.

It’s about time to re-evalutate the song. Give a listen with a haunting choral version courtesy the National Association of Partisans website; a more standard upbeat version is worth hearing here, courtesy the Marxists. Translated lyrics here.