Those rich reds adorning paintings in Pompeii were originally ochre — Italian researchers say they now think that sensuous Pompeian red is the result of an accident.

Researchers at the national science council (CNR) say the original signature color at the ill-fated city of Pompeii was probably yellow – ochre to be specific.

Before Mount Vesuvius blew its top in 79 A.D. and buried the city, it emitted high-temperature gas which turned the original yellow color that dark red. It’s not an entirely new discovery – ochre was also the main color at Herculaneum, sister city also buried by Vesuvius.

“Thanks to the investigations we have ascertained that the symbolic color of the archaeological sites in Campania is the result of the action of high temperature gas leakage which preceded the eruption of Vesuvius in 79 A.D.,” says Sergio Omarini of CNR.

“Experts already knew about the color alteration, but this research makes it finally possible to quantify to the extent of it.”

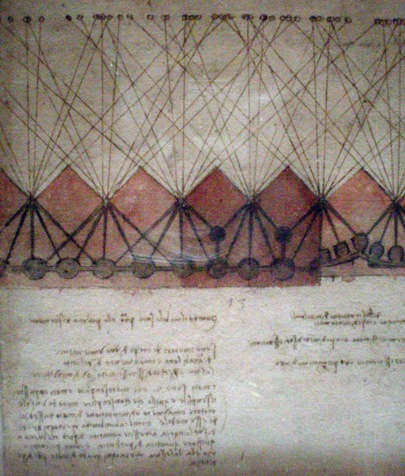

Researchers went back to texts by Pliny and Vitruvius to see how their contemporaries made red – cinnabar, mercury compound, red lead, lead compound and the rarest and most expensive pigments, mainly used in the paintings.

To check out the composition in the paintings, scientists used a non-invasive X-ray fluorescence (XRF) spectrometer that reveals the presence of chemical elements that exclude red lead and cinnabar – leading them to believe ochre was the original color.

Somehow Pompeian ochre just doesn’t lend the same tone.