The view from Galileo’s last home now looks out on Italy’s National Institute for Astrophysics, where researchers have made a model of his telescope. (Nicole Martinelli/GlobalPost)

ARCETRI, Italy — Astronomers have recreated Galileo Galilei’s telescope to celebrate the 400th anniversary of his groundbreaking observations.

Galileo spent his last eight years confined to Villa Gioiello here in the hills south of Florence after he was condemned as a heretic in 1632 for his conclusion that the Earth revolved around the sun. The small white building has a bare facade, except for a bust of the scientist staring fiercely at the Trattoria Omero across the street.

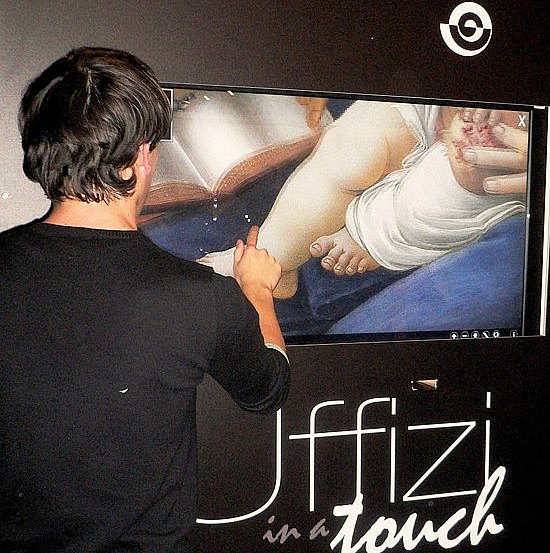

In the late 19th century, the white domes of the National Institute for Astrophysics (INAF) observatory rose within view of the Villa. Now, after two years of study, INAF researchers are observing the night sky with a replica of Galileo’s telescope.

They began trying to see through Galileo’s gaze in January 2009. While Galileo spent just one winter making his observations, researchers strung out the work over the year. Paolo Stefanini, a technician who has solved problems big and small at INAF since 1966, believes Galileo would recognize the simple metal tool he crafted.

“When we first set out to re-create it, aesthetics played a part,” Stefanini said. “But we also needed something sturdy. The original was made from strips of wood joined together and covered with red leather; we needed a telescope that could be used without falling apart.”

Like Galileo’s instrument, the modern replica is about three feet long. It magnifies distant objects by refracting light through lenses housed in a tube, with a light-gathering objective lens at one end and an eyepiece at the other.

Stefanini made his refracting telescope and tripod from spare metal parts found around the observatory. The lenses were crafted by the National Institute of Applied Optics in Florence, which measured the shape and refractive index of the originals and the National Institute of Nuclear Physics in Florence, where scientists determined glass composition using X-ray fluorescence.

Instead of one man peering at the winter night sky and making hasty sketches, however, the images are recorded by a light-sensitive silicon chip called a charge coupled device or CCD. Attached to a digital camera, it transforms photons into electrical signals, making digital versions of the images as they would form on the retina of a human observer. Starry skies captured by the replica will be published online in early 2010.

Galileo wasn’t the first to point a telescope at the heavens, but the 45-year-old-mathematics professor taught himself the art of lens grinding, making his the most powerful around. His instrument magnified 20 times, allowing him to see moon craters, identify individual stars in the Milky Way and Jupiter’s four largest moons.

Galileo spent late 1609 and early 1610 gathering information and drawing the sky; his observations became the Sidereus Nuncius (“Starry Messenger”) a treatise that led to a clash with the Inquisition.

The idea to re-create Galileo’s telescope originated on the terrace of the Institute and Museum of Science in Florence. Museum director Paolo Galluzzi took one of the two original remaining Galilean telescopes on the museum roof to inspect the night sky.

“I have to admit, I saw very little through Galileo’s telescope,” Galluzzi said. “You realize how much he accomplished by trying to see what he did, the way he did.” Galluzzi, for example, strained to spot Jupiter’s largest moons, noting how impressive it was that Galileo not only saw them but also calculated their phases.

Galileo’s telescope has a very narrow field of view: The moon, for instance, fills it entirely. When Galileo spied the blanket of stars in the Pleiades and the Milky Way, he “got tired” of trying to sketch them all, Palla said, creating a challenge for researchers to reconstruct his accurate but incomplete observations.

Galileo also had poor eyesight and vision problems. To know precisely what Galileo saw, Galluzzi wants to open his tomb in Florence to examine his DNA. If authorities grant permission, it’s up to Peter Watson, bespectacled president of the International Council of Ophthalmology, to determine whether Galileo suffered from a condition called creeping angle closure glaucoma. Galluzzi believes it might explain why Saturn has lateral bulges and not rings in Galileo’s sketches.

To follow in Galileo’s footsteps, the Arcetri Observatory team uses a photocopy of the original manuscript, which includes eloquent watercolors of moon phases made hastily on scrap paper.

Looking at the heavens as Galileo did requires more that just the equipment, however. On a recent night, thick cloud cover made pointing any telescope futile. And to minimize interference from light pollution, Stefanini spent long nights stargazing from his home nestled in the Tuscan countryside.

“Even the best equipment doesn’t guarantee much with astronomy,” said Francesco Palla, director of the observatory. “Patience is about 90 percent of what we do.”

While waiting for the sky to clear, Palla gives an evening visit to a group of Florentine 5th graders. In response to questions from the soft-spoken director, hands dart up to answer that the earth revolves around the sun, what the Milky Way is and how many stars there are in Orion’s belt — the same principles that got Galileo excommunicated.

When the kids file out 90 minutes later, the clouds have parted enough to try to frame the moon in the model of Galileo’s telescope.

Squinting to overcome my own nearsightedness, the rough surface of the moon in its first phase finally comes into view. It’s a whole new world.

This story first appeared in the Global Post, that site is now a part of PRI.org.