Battle lines have always been drawn over maps. Place names are political, cultural, temporal: from Constantinople to Istanbul and Burma to Myanmar what a place is called matters.

In the digital age, however, you have no idea who is behind the changes and why. The companies that make the maps millions of people use every day change names following opaque processes that appear to depend on who lobbies loudest at the moment. It’s a strong argument for free, public, editable maps like OpenStreetMap where both the changes and the debate are transparent.

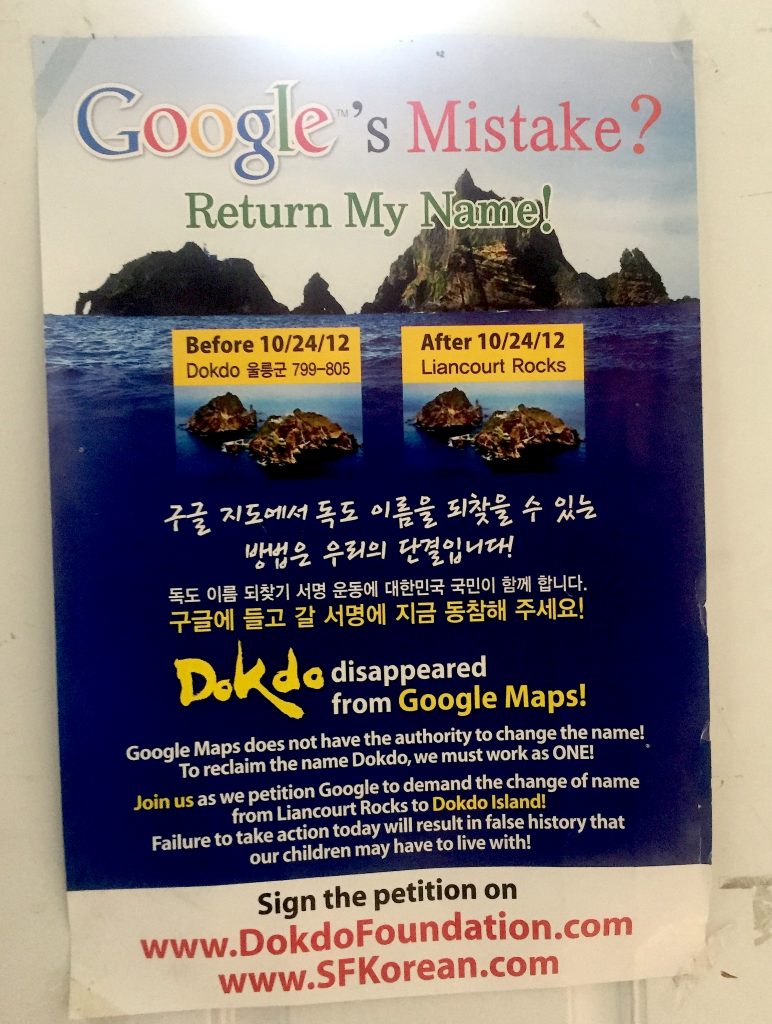

About a week ago, I spotted this poster petitioning Google to put Dokdo back on the map at San Francisco’s Korean American Community Center of San Francisco & Bay Area.

They’re a small group of islets off the coast of South Korea with a host of potential names. The Korean name for them is Dokdo, in Japan it’s Takeshima; Liancourt comes from a whaling-era French ship that almost wrecked on these jagged rocks.

In 2012, the centuries-old fight between Korea and Japan went digital and, bowing to pressure, Apple Maps and Google Maps changed the name from Dokdo to Liancourt Rocks. The drive to change it back hasn’t ebbed, as recent as April 2018 the islands cropped up in a dessert that didn’t sit well with Japanese diplomats.

The Silicon Valley companies who reside roughly 5,400 miles away from the contentious spot never publicly stated why. And if this sounds like just arcane name-calling – at stake are fishing rights, resource rights, national security rights. (The dissection of why this matters in “Prisoners of Geography” is definitely worth a read.)

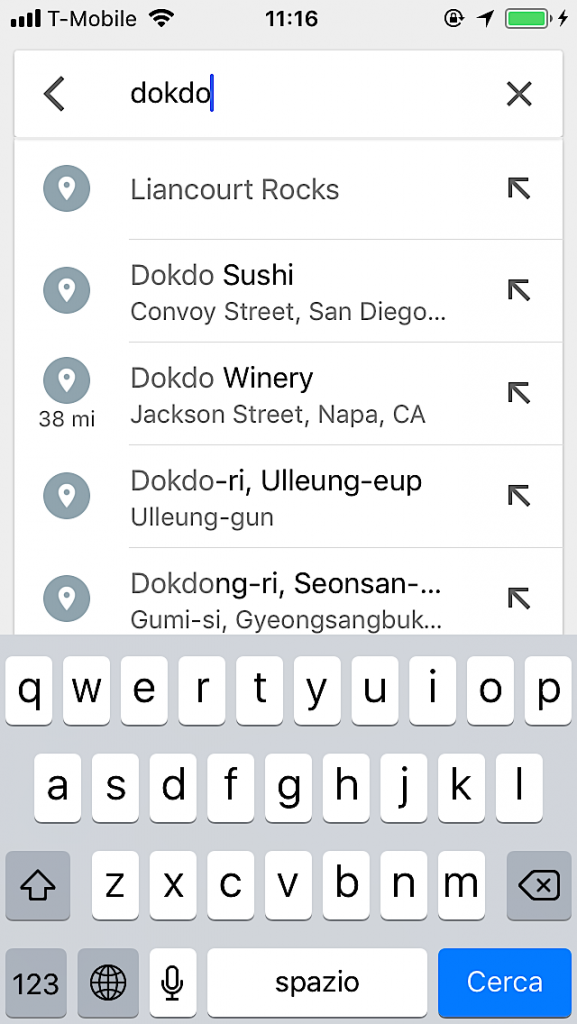

Considering the 2012 date on the poster, I wondered whether the question had been settled. Nope. Open up the map that’s an extension of your brain (aka your smartphone) and neither Google Maps or Apple Maps will get you to Dokdo.

Google does a slightly better job, at least acknowledging that the place you’re looking for when you type in Dokdo is what they’ve decided to call Liancourt Rocks.

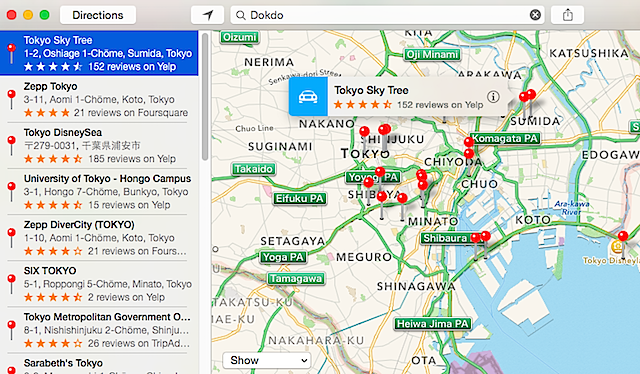

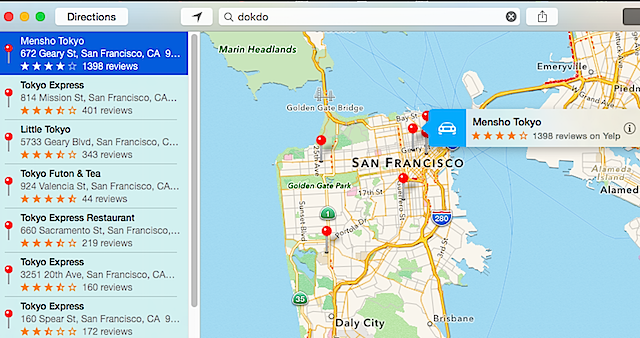

Apple Maps assumes its users have fat fingers and shows places with “Tokyo” in the name.

The exception: if you’re searching close to South Korea, it directs you to the Dodko Museum, dedicated to the territorial question.

The exception: if you’re searching close to South Korea, it directs you to the Dodko Museum, dedicated to the territorial question.

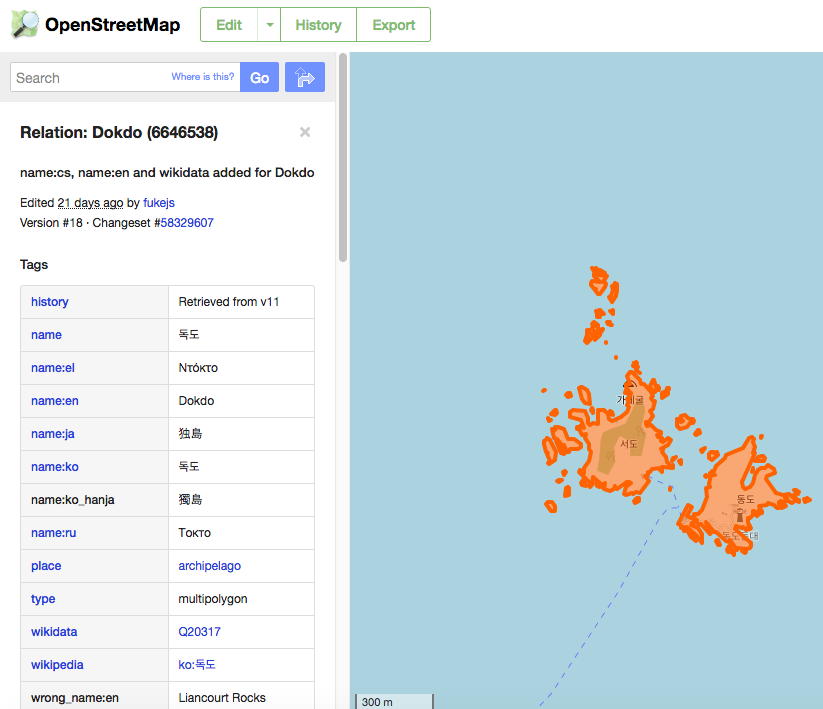

On OpenStreetMap, by contrast, you’ll find Dokdo.

On OpenStreetMap, by contrast, you’ll find Dokdo.

Even if you’re not logged in, you can see when the last edit was made. Sign up for a free account and you can see the history of the edits and join the discussion. The last tag on the page shows what the “wrong name” is.

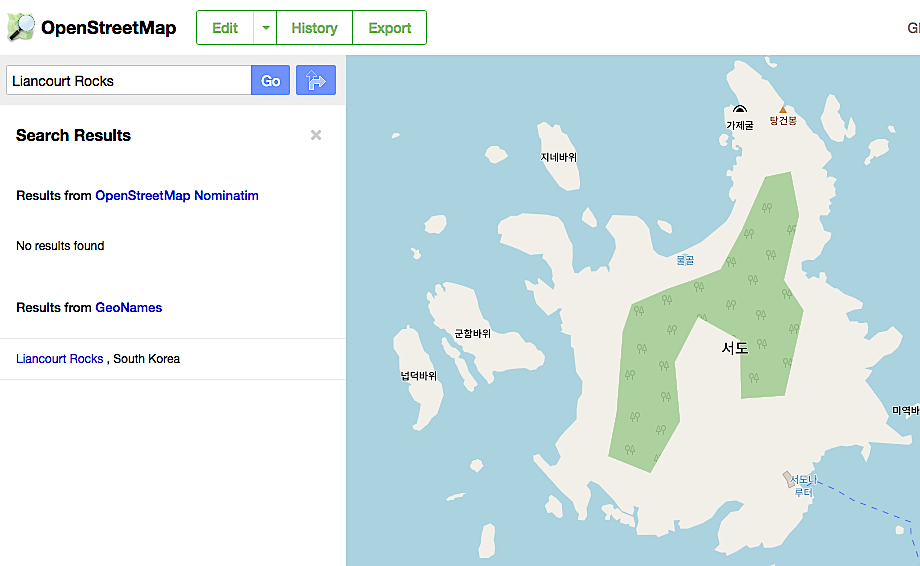

It’s not perfect. If you search for Liancourt Rocks, it’s a little confusing because there are no results on OpenStreetMap but there’s a result from database GeoNames.

It’s not perfect. If you search for Liancourt Rocks, it’s a little confusing because there are no results on OpenStreetMap but there’s a result from database GeoNames.

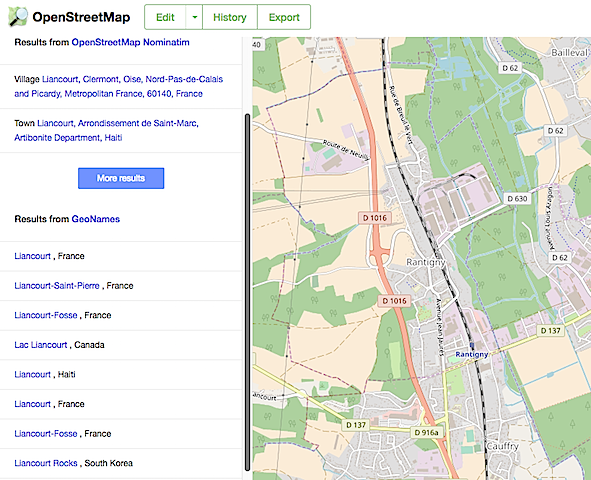

Looking up just “Liancourt” gets you two OSM results in France, with the GeoNames entries “Liancourt Rocks” rolling through France, Canada and Haiti before getting to the search term.

Looking up just “Liancourt” gets you two OSM results in France, with the GeoNames entries “Liancourt Rocks” rolling through France, Canada and Haiti before getting to the search term.

There’s a lot more to be done — for starters, getting OpenStreetMap as the every-pocket cellphone map. For an itch-scratching project, I’m testing a bunch of OSM-friendly apps (mainly for editing but most also provide navigation) and there is a ways to go.

There’s a lot more to be done — for starters, getting OpenStreetMap as the every-pocket cellphone map. For an itch-scratching project, I’m testing a bunch of OSM-friendly apps (mainly for editing but most also provide navigation) and there is a ways to go.

But until Google and Apple launch open, community-driven forums for questions surrounding map making (much like they are proprietary-driven companies but still have open-source departments) OSM willl be the fairest, most transparent public map around.