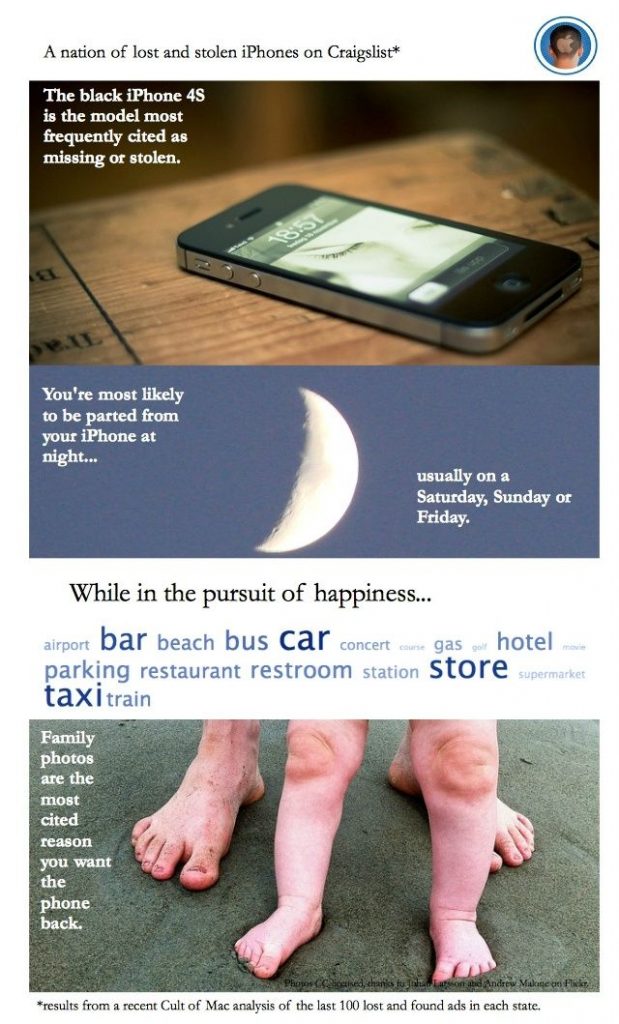

I am not a psychic, but I have a good idea where you and your iPhone parted ways.

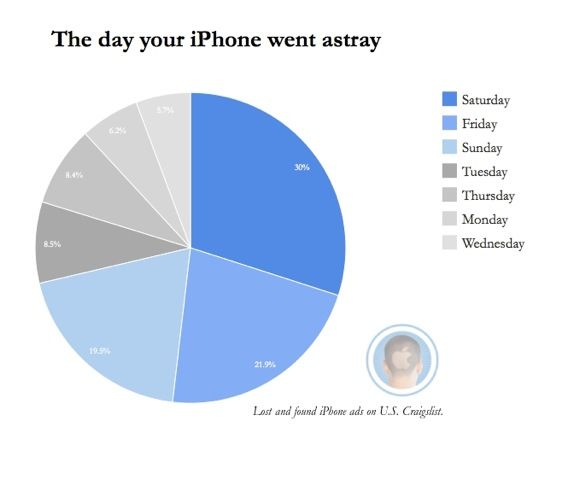

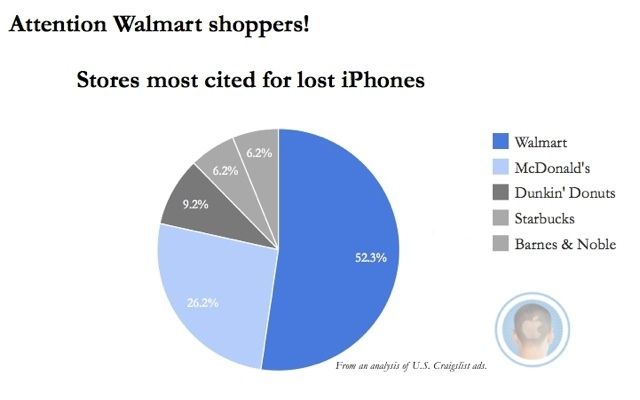

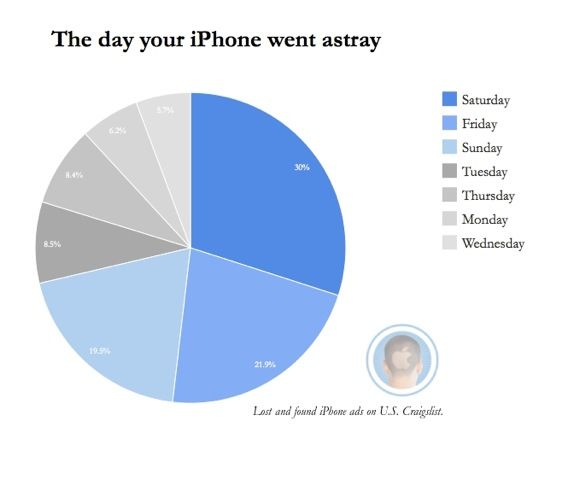

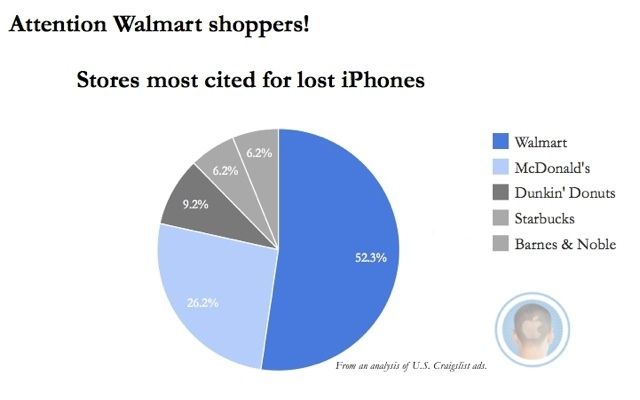

If you’re desperately seeking it on Craigslist, chances are you lost your device – or had it stolen – over the weekend, especially at night. And probably at some fun destination – shopping, the beach, a bar – or heading there on your usual means of transportation (the car, a gas station or parking lot, or bus).

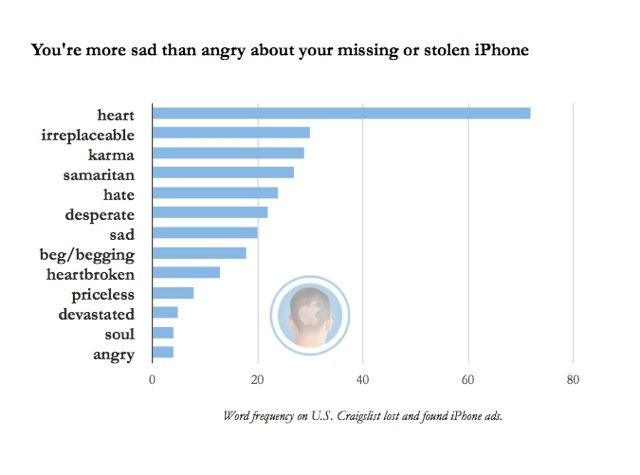

Although your entire work life might be on it, you are pleading with the person who found it (or swiped it) to return your iPhone because those photos of your dog or kid or grandma can never be replaced.

This is the most common tale to emerge from Cult of Mac’s recent analysis of hundreds of iPhone lost and found ads on Craigslist blanketing the entire United States. (Here’s the backstory on how I did it using Python, if you’re interested.)

Stealing iPhones (“Apple picking”) now accounts for about half the crimes in cities like San Francisco and New York; it’s hard to say how many absent-minded drinkers leave them at bars, but if you find a phone and don’t return it, in many places that becomes theft by finding.

Police and Apple diverge on what to do about it. The Cupertino company advises you to notify police, while some authorities are urging phone makers and service providers to add a kill switch to curb thefts.

Apple’s “Find my iPhone” can help, unless the savvy crook pops out the SIM card or wipes the contents of your phone and starts over. This gray area has inspired some derring-do recoveries, like outing the thief or the finder-who-wants-to-be-keeper by staging a diabolical seduction. Not recommended.

In the meantime, if you’re hoping someone will return your lost iPhone or realize they’ve bought stolen goods and do the right thing, you’re probably heading to Craigslist.

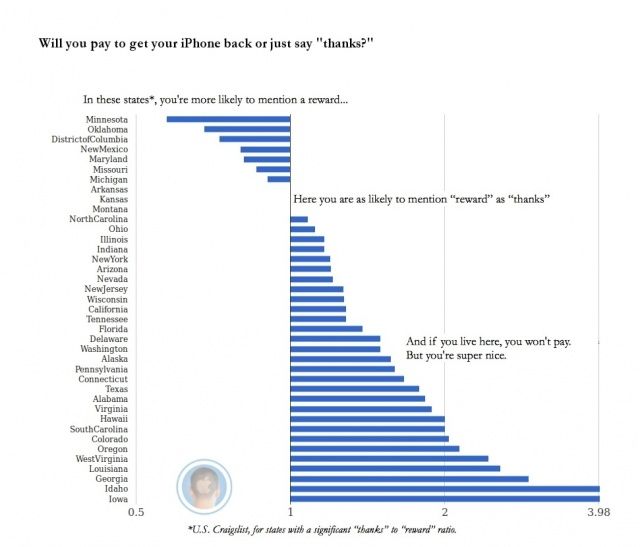

Generally speaking, you’re more likely to offer heartfelt thanks than a reward for the return of your phone. Unless you live in a place such as Washington, D.C. or Michigan, then you’re ready to bust out the cash.

After combing through these ads for the project, I bought an ugly white case for my black iPhone 4S to make it easier to see in the pitch of all of my dark bags and on taxi seats, etc. As a result, I am having fewer of those “where’s my goddamn phone?” moments.

Have you lost your iPhone? How did you recover it? Let me know in the comments.

First published at Cult of Mac.